On Confidence

Bearing, presence, gravitas, and authority are all some words used to describe those who project confidence. When I am advising executives and leaders to help them with their teams, one of the topics of concern for them is confidence and how to gain it. Or at the very least, how to project confidence even when it’s not there. The latter seems to be especially concerning to those who are relatively new in their leadership positions.

The truth is that confidence, like many things, is the product of experience. Specifically, the experience of trying, failing, trying again, and eventually learning from your experiences (even if not successful). Confidence is knowing that even if you don’t have an exact solution to a problem at the moment, you can help the team come up with a solution to any problem. A person can become confident in a specific domain, but the overall confidence that is apparent in experienced leaders is earned from challenging experiences which often resulted in unpleasant outcomes.

That is all well and good as an explanation for the origins of professional bearing and presence in experienced leaders, but for newer leaders the main concern is how to gain confidence in the first place. In other words, how can they be confident when they haven’t yet had the experience?

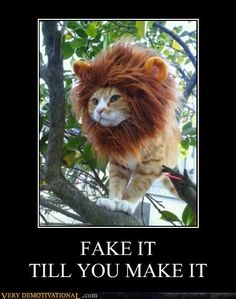

The short answer is: fake it until you make it.

Since confidence is only really expressed or noticeable upon interaction with others, we can consider what a typical interaction process looks like for leaders. By having confidence in this process, leaders will tend to be viewed as confident overall. Remember, confidence is not about having all the answers, and the process below applies to leaders generally, not just those with less experience. Confidence is about being sure that you can help the group solve a problem.

Example

Let’s assume, as an example, that you are a relatively fresh technical lead. You are directly responsible for one or more teams, and there is currently a component which must be completed in order to help a project be successful. This component has strict performance requirements in terms of processing speed and other things, so it’s not a matter of straightforward design and implementation. You are not sure how to solve the problem as you have never experienced something like this. What do you do?

Step 1: Collect information

One of the most important tasks leaders must complete is collecting the amount of information necessary to make an informed decision and direct the actions of subordinates.

This is not just a matter of referring to a requirements sheet and checking off a box. Leaders should make sure they have collected information up, down, and across the organization. This serves multiple purposes including personally getting a better understanding of the strategic landscape, making sure people’s opinions are taken into account, and also becoming informed about additional situations or motivations you may not have heard about yet. Pay particular attention to things which may explain people’s motivations. Often this is about power in the form of the size of their team, or money in the form of bonuses, raises, or similar. Also have an understanding of P&L responsibility and whether or not the person you’re talking with has some kind of targets relating to P&L numbers.

Talk to the bosses

First, it’s important to confirm that the overall vision and understanding is correct. If a problem is to be solved, and the intent of your boss is not clear, then obviously the solution may not achieve the desired outcome. If you disagree with the boss about their strategy or decisions, now is the time to ask them to help explain it to you again. This should always be done respectfully, and in the context of enabling you to better execute their vision.

Talk to the peers

Once the direction from the boss is clear, it’s time to talk with your peers to make sure they have the same understanding and also to make sure they aren’t trying to solve the same problem. It’s shocking how often multiple teams within companies try to solve exactly the same problem because they simply weren’t aware that anyone else was working on it. This de-conflicting step can save huge amounts of time, so it’s a worthwhile investment.

If another team is working on the same problem, some new leaders have concern about helping the current team complete the project versus continuing to work on the project themselves in parallel. There is often anxiety about who will get credit and whether or not the team(s) will look bad.

The top priority for your boss is that things are accomplished. In general, as long as objectives are met on time and within any specified constraints, they won’t care whether or not you personally or your team generally solved the problem. They just want the problem solved. You’ll be a lot better off working with another team to get the problem solved more quickly than trying to outrun them on a parallel track. Work together and support each other instead of trying to get credit.

Talk to the teams

After you’ve had the required conversations upwards and outwards, it’s time to talk with the teams. By this point, you should have a very broad and complete understanding of the what and the why, and it’s up to you to make sure the teams understand the same things, in context, so that they can come up with the how. In this step, you are offering perspective and guidance if needed, but in order to build successful autonomous teams it is absolutely necessary for the teams to own the solution. Ideally they should come up with the solution on their own and be totally responsible for the implementation. Confidence with the teams is almost automatic at this point since you have a very good understanding of the problem domain, the intended strategy from higher up, and the general activities of other teams which could be in conflict from a time and money perspective. Remember, it’s not your job to solve the problem. It’s your job to help the team solve the problem.

Set a direction

After these planning steps have taken place, you have the context and direction from higher, the knowledge about other projects from your peers, and some possible options for solutions from the teams. It is time to set a direction for solving the problem. This could be as simple as accepting the advice of the team(s) on how to solve the problem, and in the cases where you haven’t solved the same or similar problem before that is a likely outcome.

Sometimes though, you will have had experience solving these kinds of problems, and your past experiences can provide useful changes to the plans made by the teams. In these cases, make sure that you are providing guidance by sharing your experiences and not overly influencing the teams by simply telling them what to do. They should own the solution. Be advised that what might appear like a small suggestion to you can come across like an absolutely critical requirement to the team.

The desired outcome of this step is that given all information currently available, a direction has been set and actions can be taken by the team.

Steering

Now that plans are in motion, the primary job of the leader is to make sure that progress is consistent and that all the necessary parties are kept informed of the situation. This means regular discussions and checks with the team to make sure they don’t need anything, in addition to communication up and out.

On the topic of consistent progress, it is also sometimes necessary to adjust scope along the way. People may try to pile on additional requirements after everything is in motion. Sometimes there are additional requirements which can be added with little or no additional work by the team. There are even rare cases where additional requirements result in less work for the teams. In these situations, it’s almost always best to add the additional features or requirements. It builds goodwill with the stakeholders and ensures they take you seriously in the future when you tell them that their improvement cannot be added.

Conclusion

Throughout this process, it was not incumbent upon the leader to actually solve any specific problem. Rather, the job of the leader is to coordinate and guide the activities of the team, share their personal experiences with the team where appropriate, and help the team avoid known pitfalls. There is also a large translation component, since the vision and direction set by the leader’s boss may not be directly applicable to the individuals on the leader’s team doing the implementation. Some modifications to the message at those interfaces is nearly always required, and translating those messages to people with different perspectives is itself a huge leadership skill.

If you follow the process above, with humility, then it is only a matter of time before your team and your bosses will view you as a person with confidence and the ability to achieve objectives on time and on target.